Finding an RSS Feed Reader to Replace Google Reader

As soon as the shuttering of Google Reader was announced, I went on the hunt for alternatives. I've researched various options, both self-hosted and cloud-based. I've tested them all in parallel for over a week, and have come to a tentative conclusion.

Your time is precious, here's my decision so far: My absolute favorite is selfoss. It's fast, minimal, and looks beautiful in both desktop and mobile formats. It happened to be very easy to install, and had no trouble taking in my OPML file, and it already had the right keyboard navigation keys configured. It mostly worked correctly right out of the box.

There were two settings I changed in the config.ini file:

homepage=unread auto_mark_as_read=1

That sets up the behavior I prefer. I want the site to always start with a list of unread content, and as I navigate around, I like the articles to be automatically marked as read.

Did it say it was minimal? Oh, it is. Gloriously so. And a bit too much. It makes for a very consistent reading experience because it strips away the effect of almost all HTML elements. No embedded videos, many pictures are not displayed, all text is displayed at one size and one weight.

That won't do for me. I want to see a little CSS beautification in my reader. Whitespace between paragraphs and seeing all the video and images is important to me. I need to know when the images are there. So I made some minor changes to the codebase.

- Removed elements like strong, b, em, i and p, from the strip-all-style part of public/all.css.

- I used this technique to remove elements from simplepie's strip_html list. I allowed iframe, object, param and embed in spouts/rss/feed.php for embedded videos.

- I turned off safe and whitelisted the embedded video tags in the htmLawed object in helpers/ContentLoader.php.

- Finally, I made this change from ref= to src= in helpers/ViewHelper.php.

Having made the changes above, now the feeds in my selfoss reader retain some rudimentary style and properly display video and images.

Now that's much better. This is a selfoss installation that I can live with.

As for the runner-ups? I liked Tiny Tiny RSS a lot. But it was slower loading and responding. And the visual presentation for desktop mode wasn't as nice. There's too much clutter. Its mobile version is not supported, but ttrss-mobile is awesome. Install it into /mobile for the easiest experience. Finally, remap they keys j and k to next_article_noscroll and prev_article_noscroll with a plugin.

If I were forced to go with a 3rd party cloud-based product, I'd probably choose Feedly. It's relatively fast and minimal. After that, it's a toss-up between NetVibes and The Old Reader. I didn't pay NewsBlur to see how they'd perform with a moderately large OPML. I'm looking forward to seeing what Digg comes up with.

And as for local desktop clients? They're not in the running. I need my feedreader to be current on any screen I happen to login to.

Finally, some suggest using Twitter as Google Reader's replacement. I enjoy "dipping into the stream" as it were in Twitter, Facebook and Reddit. But I need a tool that'll save articles from my favorite friends and content creators too.

I hope you may find this helpful. If nothing else, it'll serve to pinpoint the state of the art in early 2013 for keeping track of content online.

Happy Birthday, Me. I got you Vim!

I used to play NetHack. The keyboard keys it uses to navigate your player are the same screen navigation keys for the editor vi. So I've always been able to make do with vi and its successor, Vim.

I've recently decided to give Vim a serious look, since it's still ubiquitous after more than 20 years, (I find myself having to ssh to remote computers more often then I expected), and I have really smart, productive colleagues who use it everyday. Somehow, it has stood the test of time. Vim is one of those tools that increases in value exponentially if you invest the time to become proficient in it.

So, in the grand tradition of giving myself strange intangible gifts like giving myself data portability a couple of years ago, this year, I decided to invest some time in Vim.

I'm still new to it, but I've tasted the change in mindset that happens as you get better and better at Vim. It feels like you're programming the act of text editing, and I mean that in the best way possible. (This is coming from a guy who spends his free time programming cron jobs.)

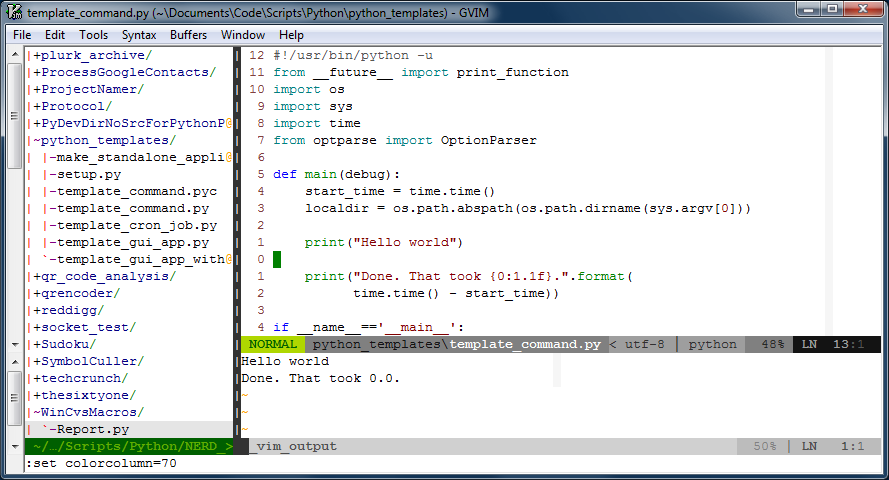

Time for a screen shot of what Vim looks like for me when I'm working on a shell command. Click on it to see it at full size.

There are three "windows" in the image above. The window on the left is a tree-view of the files on disk. That window is managed by a script called, NERDTree, and it's usually closed. I only open that when I need to look at another file. On the right are two windows, one above the other. The larger one is on top, and is the "main" window that hosts the main buffer that I'm actively editing. The smaller window on the bottom is an "output" window, that prints out the results of the script I'm editing whenever I run it.

That image represents an iterative workflow where I edit (possibly multiple buffers) in the biggest window, hit <F5> to run the script, and see the output displayed in the window below. It's a workflow that works well for small scripts.

There are a few things about that window that I'd like to point out:

One:The line numbers are relative to the current position of the cursor. This is really handy because Vim's normal mode commands work nicely with line number counts. The line numbers change automatically to absolute line numbers when the window loses focus. That's accomplished by this bit in my .vimrc file:

autocmd FocusLost * if &relativenumber | set number | endif autocmd FocusGained * if &number | set relativenumber | endif

Here's a great explanation for why to switch between relative and absolute line numbers in vim.

Two: There's a very subtle light gray column at column 70 in the image. Usually it's at column 80, but I bumped it in to take the screenshot. That column helps remind me to keep my code lines short.

Three: There are a few plugins doing work behind the scenes. You can see one called powerline just under the main window. Powerline is a very handy status line. What you can't see in the image are other plugins like taglist that help when one is developing code. Vim also support syntax completion.

Four: Vim is very customizable, and it sometimes needs it. For example, I like the behavior from setting smartindent, except when it un-indents the # character to the first column of the line. In Python, the # character starts a comment, and I want it to remain in the column in which I put it. Here's what I've added to my .vimrc file to fix that issue:

set smartindent autocmd FileType python inoremap # X<c-h>#

Boo that Vim doesn't always do what you want out of the box. Yay that it always can be fixed to work the way you'd prefer.

Five: Vim lets you continue to undo actions from your previous sessions with the file, if you like. Isn't that an awesome option to have? If you want it, the option to set is:

set undofile

Far better than what I've written here, I strongly recommend Steve Losh's article, Coming Home to Vim. He's got a lot more experience with Vim, and he makes a compelling case for it.

It's a work-in-progress, but I'm willing to share what I've got so far in my .vimrc file. You'll see that I customize far more than I mention here in this article. Once it's stable, I may maintain it in a repository at github.

The Well-Mannered Daemon

The subject line is a bit of a lie. It's not a well-mannered daemon so much as it is a well-mannered cronjob. But it's more fun to say daemon.

I had to make a new cronjob. As is occasionally the way with things, NetFlix saw fit to remove their AtHomeRSS feeds. I used that feed at my lifestream, so I needed a replacement.

I rebuilt the AtHomeRSS feed, and I made the complete source code available. Disclaimer, it's code that was written between 11:00pm and 2:00am over a couple of nights. You get what you paid for.

The point of the repository over there at GitHub is the new script that makes an RSS feed by scraping email. But still, I thought it was interesting how much code was dedicated to making the cronjob be well-mannered. I expect my daemons and cronjobs to have the following attributes:

Accountable

Do the job quietly, and write a short status report on how it went. No need to interrupt me if things went fine. But I do want to be able to check-in on it, and know if anything interesting happened. My cronjob writes a line (or more) to a status file every time it checks the email. It also trims away really old entries from the file, keeping it short.

Diligent

If it does encounter a problem, I want it to let me know right away. That's not something to just put in the status report. It should ask for help and email me with any problems that it doesn't know how to handle itself.

Adaptable

When I need to give the cronjob new instructions, it should be easy. It shouldn't fastidiously insist on writing reports or sending me emails as I'm in the process of giving it new directives. This cronjob allows me to quickly test changes with a --debug flag.

Dependable

This last trait is mostly just thrown in there. It automatically applies to all software, since you only have to write it once, and all things working correctly, it'll do what you tell it to. Still, that's what's beautiful about software. Any time I find myself repeating a task, I find myself wondering, could I just automate this?

There's an interesting description that accompanies the photo that I used as the header for this image. The photo is of "Machine with Concrete." Ars Electronica writes, "Arthur Ganson (US) reminds those partaking of it that the human being is the only creature on Earth to build machines that (are meant to) outlive their creator." My daemons and cronjobs are meant to outlive me.

Photo by Ars Electronica / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

My Location Predictor

I made a web page that predicts where I'm going. It was a fun little academic exercise, and I thought some of the challenges were interesting.

Ever since it came out that Apple was tracking and keeping location data on everyone's iPhones, and owners could get to that data my curiosity was piqued. Apple was quick to stop tracking so much data and to limit access to the database, but I saved off my phone's database of locations while I could. Later, I installed a new app, OpenPaths, that intentionally and continuously logs my phone's locations and makes that data available to me.

Now that I was logging my phone's locations in the background, I could ask myself what I wanted to do with the data. I knew what I wanted to do right away! I wanted the computer to answer the following question:

Given where I've been, where am I probably going now?

I'd make a webpage whose only job it was to display its answer to that question. It's a simple web page to look at, but the devil's in the details.

Sensible Predicting

The human brain is wonderfully better at answering that sort of question than the computer. It's a matter of pattern recognition across at least three dimesions: time and two-dimensional space.

I started with the way I'd think about answering that question:

If there aren't any notable exceptions, like travelling for work or vacation, then I follow a bi-weekly schedule more closely than a weekly schedule. So I'd look at where I was at this time of day two weeks ago.

To translate that into an algorithm for the webpage a few things need to happen. I have to codify what a "notable exception" is. Perhaps it's being more than 100 miles away from home for more than a day or two. Or, if I'm currently away on vacation, then the program shouldn't be looking at what I've been doing two weeks ago at home.

Here's the algorithm that the computer uses:

- If I was near here two weeks ago, consider where I was going back then at this time.

- Otherwise, consider where I was at this day of the week last week.

- If I was away on each of those occasions, then how about where I was yesterday at this time?

Simple enough. But the question of "two weeks ago at this time of day" itself is a bit ambiguous. Two things get in the way of that that the human brain just automatically figures out. One, time-of-day is local. If I am in California today, but I was in Hawaii two weeks ago, I can pretty easily calculate "breakfast time" for either. But the computer would have to first translate latitude and longitude coordinates into time-zones on the Earth. Then it'd be able to calculate relative time-of-day for either week at either location. The other issue, daylight savings time throws off the way a program might naïvely calculate "two weeks ago."

Account for daylight savings time

"Two weeks ago at this time of day" is a loaded phrase. The naïve approach for a computer that keeps track of time by incrementing seconds would be to subtract the number of seconds in a day, and do that 14 times. But that doesn't account for daylight savings time, which would throw off the results for 4 weeks out of a year.

My program uses Python, which has a library to translate time from epoch timestamps (which are used by OpenPath's library) to a calendar date and time-of-day format that's more native to the human mind. So the actual code calculates "number-of-seconds to this time-of-date two weeks ago" as follows:

now - time.mktime((datetime.fromtimestamp(now) -

timedelta(days=14, hours=0)).timetuple())

Huh, that's sort of wordy compared to the naïve alternative, but the important thing is that this approach is always correct. Once we've figured out when "two weeks ago" actually is, then we can calculate what "where" and "how far" actually mean...

Distance Calculations

If you're near the equator, then calculating short distances using latitude and longitude can be approximated by an equation based on Pythagorean Theorem. What's funny is that if you search the web looking for the algorithm in Python, you'll usually see something like the following function:

def distance(p1, p2):

return math.sqrt((p1[0] - p2[0])**2 + (p1[1] - p2[1])**2)

But as long as you're importing the math module anyway, it'd be even more direct if you just used math's own "hypot" (short for "hypotenuse") function:

def distance(p1, p2):

return math.hypot(p1[0] - p2[0], p1[1] - p2[1])

But that calculates planar distance, and we're not on a plane. We're essentially on a sphere. So it's better to use the Haversine formula if we want to get an accurate distance between two points defined by latitude/longitude coordinates.

Now that timedelta and the Haversine formula handle the "when" and "where" in my fuzzy algorithm, it's time to take a look at the presentation of the data.

The Webpage Itself

So much for the algorithm. What about the quality of the webpage itself?

Responsive Webpages

It's a small webpage. So it's only sensible and intuitive that it'd be a quick and responsive webpage, too. But the webpage wouldn't work without making relatively long queries to two remote services.

- Retrieve new location data from the remote OpenPaths API service.

- Retrieve specific map data from the Google Maps API service.

In between the two big remote queries, the program needs to perform the actual prediction for where I'm going to be based on the OpenPaths data, and send the predicted points to Google Maps. There's no way to avoid the fact that the webpage is going to take a few seconds to do all its work.

The best work-around for that is two things:

- Ajax. The web server can quickly serve a simple HTML web page to the client which'll get displayed for the user right away. Then the browser can make another request to the server for just the data that takes a long time to calculate and retrieve.

- Caching. Once I've retrieved raw datapoints and made the prediction calculations, then that prediction shouldn't change for a few minutes. I can save off my prediction and immediately hand it back the next time the webpage is requested, if it's requested relatively soon.

Well-behaved Webpages

It's critical to me that the webpage be small and simple. It has to get to the point as quickly as possible. But it's also important to me that I give credit to the tools and services I used to make it possible. That called for some credits to be put in a footer.

I wanted the footer to be relative to the browser's window viewing the page. But if that window was too short, then the footer would end up overwriting or being overwritten by the map or the text above the map. The fix for that was some clever CSS that put the footer at the bottom of the window, but never let it cover up the important part of the page, the map.

So far so good. But then I discovered something unexpected...

Bad Data

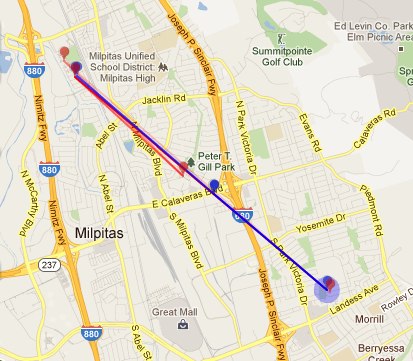

Sadly OpenPaths seems to collect bad data from my phone occasionally while it's at rest. All of the recorded and predicted movement in the map below is due to bogus data from OpenPaths.

All of the points along the same angle that extends to the south east are bad data. The phone didn't go anywhere all that time. I have no idea why it sometimes pretends to travel to that part of town, but I don't like it. This called for another interesting algorithm that's better suited for a human brain:

If the datapoints smell fishy, don't use them.

It's really easy for me to detect which datapoints are bad, and not only just because I know where my phone's been. It's because there's a certain pattern, the angle and distance traveled by the bogus points. So I've got a work-in-progress algorithm the elides points that smell fishy.

A Secret Mode

The main point to the site was the prediction. But as long as I had all this historical data, it seemed like a shame if I couldn't easily look it up, too. So there's a secret mode, impossible to find and discover. (Since nowadays people don't read long blogs or actually type in the URL bar of their browsers.)

If you add an HTTP "GET" parameter, t, to the URL, the website will return a corresponding location history instead of a prediction of where it thinks I'm going to be. t can take one of three different forms, a UNIX timestamp, an RFC 2822 date and time, or a negative number of days to look back. Here are some examples:

https://david.dlma.com/location/?t=1279684897

I flew in to Los Angeles on that day. Timestamps are good if you're already dealing with them or want a relatively short token to represent an absolute time. Otherwise, they're an epoch fail waiting to happen.

https://david.dlma.com/location/?t=2012-02-20T13:30:00

Took the kids to Disneyland that day. Fun! That date format is handy if you want to browse my location history and are thinking in terms of calendar dates.

https://david.dlma.com/location/?t=-7

What'd I do last week? This is handy if I don't need an absolute time and date, but just want an offset from the current time and date.

Finally, I've got a micro site that was really fun to build and with which I'm quite pleased.

My Dead Man's Switch

I wrote a dead man's switch to update some of my online accounts after I die.

What It Is

The basic idea is that if I pass away unexpectedly, I'd want my online friends to know, rather than for my accounts to go silent without any explanation at all. I wrote a program to take notice of whether or not I seem to still be alive, and once it's determined that I've died, it'll follow instructions that I've left in place for it. It'll do this over the course of a few days. Well, I won't tell you when it'll stop, that'd be taking some of the surprise out of it.

Two things caused me to do this. First, I wrote a lifestream. Essentially, I already wrote a computer program (a cron job, technically) that takes note of nearly everything I do online already. It was a handy thing to have, and it seemed like it could do just a little bit more with hardly any effort.

Second, I read the books Daemon and Freedom™. A character in those books also wrote a program (a daemon in his case) to watch over its creator's life, and then to take certain actions upon its creator's death. The idea got under my skin, and I just had to write a similar program of my own.

How It Works

This section will get technical, but it'll be of interest for those who also want to write their own.

Everything is in Python. The lifestream I have uses feedparser to read in and process each of the feeds affected by my online activity (sometimes called user "activity feeds"). It stores certain information in a yaml file. Here's an excerpt from the file itself.

-

etag : 2KJcCROqtyI4nqaQEg34109rfx4

feed : "http://my.dlma.com/feed/"

latest_entry : 1326088652

modified : 1326090583.0

name : mydlma

style : journal

url : "http://my.dlma.com"

The most relevant item in the file is that there's a field called, "latest_entry", and the data for that field is a timestamp. The latest "latest_entry" would then be the most recent time I've been observed doing anything online.

Given that, all I had to do was write a new script that watched the latest "latest_entry", and when it became too long ago, it would assume that something bad had happened to me. (Which would be wrong, of course, if I was merely vacationing in Bora-Bora, and didn't have internet access for a couple of weeks.)

This new script would do something like the following:

- Continue to step 2 if David hasn't done anything online for a few days. Otherwise keep waiting.

- Decide which posts to make at which times, and make note that those posts themselves don't now make it look like David's still alive and that the switch should deactivate.

Once the script thinks I've been offline for too long, it writes a cookie to file, and then goes from watching mode to posting mode.

In posting mode, the script looks over its entire payload of messages to deploy. I used the filesystem to maintain the payload, much like dokuwiki does. (Others might think that a database would be preferable. Sure, that'd be fine, too.) My payload files encode data into the filename, too. The filename is composed like so: [delay_to_post]-[service_to_post_to]-[extra_info].txt. That way, when I display a listing of the directory, I can see an ordered list of which messages go when.

Message Delivery

Messages that go to blogging services like WordPress or Habari use the AtomPub API. Messages that go to other services generally use OAuth 2.0 for authentication, then use a custom API to deliver the message.

Once a message has been successfully delivered to its service, it gets moved or renamed in such a way that it's no longer a candidate to get delivered again.

Development Process

The script runs as a cronjob, and usually just updates a status file. If it runs into a problem, it sends an email. (Fat lot of good that'll do if I'm already dead. But while I'm still alive, I'd like it to let me know if it's not happy.)

While I'm alive, I might still add posts to post later. When I add those new messages to post after my passing, I need to ensure that I didn't do anything wrong. (For example, the Habari payload is contained in an XML CDATA section, but the WordPress payload is plain XML, so I can't write any malformed messages.)

That's why as a part of routine maintenance, my dead man's switch also does payload data validation.

During script refactoring, I may want it to display certain diagnostic info directly to stdout. For that case, the script has optional debug, test, verbose and validate flags.

Risks

There's always the false positive, where it thinks I've died, but the rumour was greatly exaggerated. I'm actually looking forward to a few false positives, because they'll remind me that the dead man's switch is actually still running.

Another serious risk is that my dead man's switch relies on the successful continuous operation of my lifesteam script. There's an element to that lifestream script that degrades over time. Hopefully, I'll get around to mitigating that risk.

And yet another risk to my dead man's switch is continuously changing APIs. As I upgrade my Wordpress and Habari blogs, will they still accept AtomPub like they did when I wrote the switch in 2012? Will Twitter and Plurk still use the same OAuth protocol and API calls? Heck, will Dreamhost not upgrade Python to a version that's incompatible with my script?

Will I still have active accounts at the time of my passing? Will it then be illegal to continue to function online after you're dead? (Some bozo might die before me and do something stupid after he passes.)

There's a lot that could go wrong. But if these things don't go wrong, and my dead man's switch works correctly, that'd be pretty neat.

Have I got things to say to you!

Photo by matthileo / CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Entries

Entries