Your Last Project before the Covid Shutdown

Remembering March 2020

The Covid-19 shutdown was four years ago, and everything just before seems like a blur. Do you remember what you were doing right before everything shut down? Would you want to look it up if you could? GitLab keeps a history of contributors' activities, and I looked up what I was doing.

I had created a simple project: a service that would text me when a website changed, watch-url.

So here's the thing: I'm fundamentally against having to make a service like that. I feel like any site that relies on something changing should have an RSS feed or a web service that clients can query. I try to make that clear in the Before You Start section of the README.md. So my making this thing was under protest.

Salesforce Tower Tours

At the time, Salesforce Tower in San Francisco was occasionally offering tours to the top. To get on a tour you signed up at a site, salesforcetowertours.com, when they had openings. Problem was there was no telling when they'd update the page to allow sign-ups. Anytime they opened the site for reservations, it'd fill up in minutes, and the page would revert to the "Please come back later" page.

It was practically impossible to get reservations. My wife had been trying for weeks, and was on their email list, but it wasn't getting the job done. Their site didn't have an RSS feed or a web API. So I wrote that little web service so my wife could learn when reservations were available again. It was all for Salesforce Tower tours!

Then the U.S. shut down for Covid in March 2020, and there were no more tours to the top of Salesforce Tower. There was no more point to my little script. Oh, well.

Nudging a favorite site to get RSS

Since I decided to open-source watch-url, I chose a better example site to watch in the README, not the Salesforce site. I chose Nicky Case's ncase.me, because her site is amazing, everybody should visit it, and it tragically didn't have RSS, so some fans wouldn't know if/when she posted something new. So I used it in the README example setup:

./watch_url.py https://ncase.me/

It was my way of saying that I loved her site, and I wished there were a better way to get notified whenever she updates it. (Since you can't always trust email, as Cory Doctorow pointed out when 2600's HOPE email got filtered away by Google.)

Later On, an Unexpected Win

So here I am in January 2024, reminiscing about February 2020, and bemoaning that we may never get on a tour to Salesforce Tower.

But guess what? Nicky Case added RSS to her site! I subscribed! And now I get notifications for her new posts. That's a win!

Photo by Bru-nO / Pixabay Content License

Ways to Break a Dollar into Change

I'm going to retire a technical interview question that I've had ready to ask, but turns out to probably be too difficult. It's more a wizard-level interview question, or a casual technical discussion with peers who don't feel like they're under the gun.

How many ways are there to break a U.S. dollar into coins?

It seemed appropriate to ask this to some candidates, because once you know what you're trying to do, the algorithm in Python naturally reduces down to five or six lines of code.

def ways_to_break(amount, coins):

this_coin = coins.pop(0)

# If that was the last coin, only one way to break it.

if not coins:

return 1

# Sum the ways to break with the smaller coins.

return sum([ways_to_break(amount - v, coins[:])

for v in range(0, amount+1, this_coin)])

print ways_to_break(100, [100, 50, 25, 10, 5, 1])

You could click on the gist with more comments and better variable names if you want to try to better understand that. It's not meant to be production code, it's a whiteboard snippet made runnable.

Here's what I hoped to look for, from the candidate: After maybe clarifying what I wanted, ("what about the silver dollar or half-dollar coins? Did you want permutations or combinations?"), the problem should seem well-defined, but hard. Then, I'd hope the candidate would break it down to the most trivial cases: "How many ways are there to break 5¢ if you have pennies and nickels? How about 10¢ with pennies, nickels and dimes?" Can these trivial cases be used to compose the bigger problem?

At that point, different areas of expertise would appear. Googlers might start jumping towards MapReduce, and already figure that Reduce is simply the summation function because the question is "how many", and have the thing worked out at scale.

Imperative programmers, having thought about the simplest cases, probably clue in that there's an iterative approach and a recursive approach.

Pythonistas who prefer functional programming probably have reduce(lambda x, y: x+y [x, y in ...]) ready to go.

That got me thinking. I didn't see the need for reduce and operator.add and enum. My solution above isn't above criticism, but I think it's easier to read than some of the alternatives. In truth, it really depends on who that reader is, and how their experience has conditioned them.

While writing the algorithm, I searched the question online, and was pleasantly surprised to see Raymond Hettinger mentioned for solving the puzzle. He's a distinguished Python core developer. Too bad he probably didn't have Python then, in 2001, to help him solve the problem in a scant few lines.

Taking it up a Notch

Adam Nevraumont proposed the following challenge:

Drop the penny, and try to break $1.01. The Canadian penny has been retired, after all.

He provided the answer: Check that the remaining coin can break the amount. Don't assume it can. This also relieves the restriction that the container of denominations be ordered!

def ways_to_break(amount, coins):

this_coin = coins.pop()

# If that was the only coin, can it can break amount?

if not coins:

if amount % this_coin:

return 0

else:

return 1

# Sum the ways to break with the other coins.

return sum([ways_to_break(amount - v, coins[:])

for v in range(0, amount+1, this_coin)])

print ways_to_break(100, [1, 100, 10, 50, 25, 5])

(It's actually more efficient to pop the largest denominations first. But I wanted to show that you can use an unordered container now.)

Photo by Ian Britton / CC BY-NC 2.0

The Smallest GitHub Fork

Not gonna bury the lede: I forked a project in GitHub to change a color in a colorscheme. That's basically a tiny one-word change.

I changed jobs a few months ago, and I have the longest commute yet. I far prefer working in the office, but I don't want to have to be in the office to resolve any little emergency. So I set up my environment to be able to work from home.

First, there's access to work's VPN. Absolutely no problem there. That's the first thing everybody needs to work from home.

Then, just in case I need to see my work computer's desktop, there's VNC. I got close, but no cigar.

![]()

I set up a server, and can connect via multiple clients, but they all have the same blitting problem when it comes to launching applications. No big deal, there's another way to skin that cat.

If I can't see my work computer's desktop, I can still run its GUI applications via X11 Forwarding. That's pretty good, but those apps always look a little weird on the client side.

Then there's the last resort: good old ssh with a text-based editor. And in my case, that's vim. Low-bandwidth, and gets most of the jobs done.

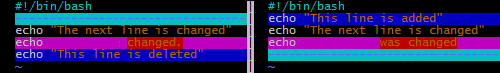

There was a problem even with that last resort. In the color scheme I use, sometimes words would become invisible when running vimdiff. It depends on the context coloring of the source files. In the following screenshot, there are words in the fuschia line that we can't see.

It's an easy-enough problem to fix. The normal thing to do is to find the configuration file, desert.vim, and change the offending color to not be fuschia. Then you're done, your problem is solved.

But I'm a developer, and to my mind, this stinks of a bug. And if it affects me, it could affect others, too. So the right thing to do is to fix the bug in a public fork, and possibly share the fix with a pull request.

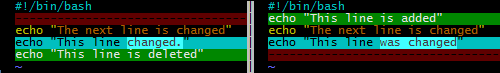

I found the original repository, and made my fork. I fixed the bug. Text on the changed lines would now be visible. While I was in there, a couple of other changes wanted to be made. I made deletions muted red, and additions green. But without a screenshot, visitors wouldn't know how the change looks. So I made the screenshots.

(Both screenshots here look a bit garish. The screenshots don't reflect what a real vimdiff would look like. In practice the improved scheme works much better for me.)

Since I now had the screenshots, I updated the README file to show the effect of the change in place.

I committed my changes, and thought to myself, "isn't it interesting the lengths developers will go to, to fix little problems and document those fixes? And how a tiny fix can grow into something larger?" I oughtta blog about it.

Dad's Project in the Garage

There's a trope about the dad who works constantly on his favorite old piece-of-junk project in the garage. He may never get it running, but getting it running is not the only point of the project. A bigger point is that it's the thing he goes to to clear his head and recharge. It's something that he can focus intently on, and it's something that's entirely in his domain.

I have a number of slow-burning projects at home, too. But they're not in the garage, they're in the cloud. Usually, they're web services. At work, as part of a team, I write code that goes on embedded devices. But at home, the entire product is mine. It's my chance to be a "full stack" engineer, the CEO, and principal customer all at once. It's nice to take on these different roles.

Updating a File

Let's take a quick look at updating a file. It's one of the most useful and common operations in programming, so it's really very well understood. A naive Python snippet to update a file with new data would look like the following:

with open(filename, 'wb') as f:

f.write(data)

What's beautiful about it is that it's cross-platform, and Python's "with" statement takes care of closing the file that was opened, even if an error occurs when writing the data.

But when you deploy code into the real world, you have to dive deeper, and think about what really can go wrong. For example, the automatic closing of the file I mentioned above? Python flushes data to the file, but doesn't necessarily sync the file to the physical disk. And in my case, it really does have to be cross platform, and I can only have one process access the file at a time, and I don't want IO errors corrupting the data. That means finding a cross-platform file lock, doing all the work on the side, and atomically moving the side file to the production file. The following snippet (elaborated a little more at this gist) fixes those problems.

with filelock.FileLock(filename):

with tempfile.NamedTemporaryFile(mode='wb',

dir=ntpath.dirname(filename),

delete=False) as f:

f.write(data)

f.flush()

if platform.system() == "Windows":

os.fsync(f.fileno()) # slower, but portable

if os.path.exists(filename):

os.unlink(filename) # or else WindowsError

else:

os.fdatasync(f.fileno()) # faster, Unix only

tempname = f.name

os.rename(tempname, filename) # Atomic on Unix

On the one hand, it's no longer a two-liner. On the other hand, I've got a function that works in all the environments I need it to, and I know exactly how it's going to behave in any exceptional situation.

Removing a Photo from a Web Album

My latest project is a web-based photo album. I could pay Flickr, Google or Apple for their web albums, of course, but they've made UX changes I don't like, and their costs are too high. So, I'm writing my own. It'll never be as polished as the production photo albums, but it'll be my jalopy, and I'll be able to tweak it in any way I choose.

One of the things my album owners need to do is delete photos they no longer want in the album. So, how should I implement that?

os.unlink(photo_filename)

That's the command to delete a file. You know it's not going to be that easy. Since we're talking about a web album, we'd want to consider a few things. We want an ideal user experience. It has to be fast, they have to be able to change their minds later, and concurrency can't be a problem. Here are some of the steps involved in deleting a photo from the album.

- Use JavaScript to make them confirm their choice in their Browser.

- Schedule the deletion of the entry in the local metadata file. It'll be done in a side thread or at a later time. Just make sure the user's web page's data refreshes quickly.

- Add a new entry to a list of timestamped-files-to-be-deleted-in-a-month.

- Run a cronjob that works on a regular cycle that actually does timestamp checking and the physical file deletion. (It's actually an S3 key deletion, which gets propagated to multiple cloud static-file servers behind the scenes. Even more remote complexity is encapsulated behind a single function call.)

What almost looked like it'd be a one-line call turns into JavaScript, AJAX, worker-thread creation, data file manipulation, and a cronjob with its own health and status reporting scheme.

This is fun! Amirite? This is what working on your own personal project is all about. So let's dive a little more deeply into step 2 above.

When the user confirms deletion of a photo, the first thing that should happen is that they get feedback. The photo needs to disappear from their view immediately. This happens before the server actually deletes the photo from persistent storage. JavaScript can manipulate the DOM right away in their browser. Over on the server, let's say you want to remove a photo's filename and its metadata from a list of photos.

Removing an Item from a Container

The task of removing the photo data from a list can be simplified to the task of removing a record from a container (l) when the first field of that record matches a certain criteria (s).

There's the loop:

for item in l:

if item[0] == s:

l.remove(item)

break

That's a straight forward imperative language neutral non-Pythonic implementation. Iterate across the container until you find the item, and then delete it right away. Unfortunately, l.remove(item) is another O(n) function being called inside an iteration of the list. That can be fixed with the enumerate call:

for idx,item in enumerate(l):

if item[0] == s:

del l[idx]

break

This is better. The enumerate() call returns an index that allows us to use the del call which takes only O(1) time.

Although that'd work, let's try to find a more modern and efficient solution. Use the enumerate call in a generator that returns the index of the item to be deleted:

idx = next((i for i,v in enumerate(l) if v[0] == s), None)

if idx is not None:

del l[idx]

The generator call is very efficient, and maybe we're done. No we're not! You see, it's a trick question. The actual answer is:

DELETE FROM l WHERE f = s LIMIT 1;

When it's your own project, you can change the domain! The data never had to be in a container that Python could process. Why not store it in a SQL database? Or, hey, just for grins, why not keep it in Python, but why was the container accessed like an unordered list? Was it ordered? Then do a binary search.

idx = bisect.bisect_left(l, [s, ])

if idx != len(l) and l[idx][0] == s:

del l[idx]

Nice, O(log n). Or, wait. Maybe it doesn't have to be ordered. Each photo has a unique filename. That's a key. Each photo's data could be a record in a Python set. Python has a "set" container that resembles mathematical sets with all the performance features you'd hope for. So let's make "l" be a set, and "r" be the row that has s in it, then...

l.remove(r)

Yay, that'll usually occur in constant order time! So have we found the best solution?

Of course not. We can make the theoretical problem as simple as we like. But in practice, the web album sometimes wants a database with different primary keys, sometimes it wants an ordered list of items, and sometimes it only needs a set of unique items.

For that matter, sometimes my user will be on a desktop computer, sometimes they'll be on a tablet, and often they'll be on their phone. That's a lot of CSS to experiment with.

That's what fiddling with your own personal project is all about! Dive deeply into whichever problem piques your interest at that moment. Make something work better. Even if the rest of the world doesn't know why you bother. Sometimes it's just what you need to be doing.

Photo by tashland / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Choosing a Cloud-based Backup Solution

Here's a comparison of some potential cloud backup solutions. I'd like to backup some desktop application settings to the cloud, user content from all the members of my family, and content from our mobile devices. It seems like every member of my family has different tastes in music, and we can't stop taking videos and photos.

Dropbox

Dropbox is a great tool, and it solves the problem of storing user content in the cloud. And it's free for the first 2 to 18 GB. (That's why the Dropbox line is blurry. The amount you get for free depends on what you do for them.) But it becomes $10.00 a month after that up to 100GB. and then more after that. And it doesn't backup certain non-Dropbox directories.

Microsoft SkyDrive offers a handy comparison of similar services, and it compares favorably in many cases. But all the services have similar drawbacks with regard to which media get backed up, and how media is shared or not shared across different accounts, each of which has to be paid for individually. By the way, you can check your current Google Drive storage here.

iCloud

For the members of the family that have iOS devices, we could backup to iCloud for free, up to 5GB. I really like that the backups would be effortless. But 5GB isn't very much for our photos, videos, and music nowadays. If we need more space, we could upgrade an iCloud or more, and our devices could share iClouds, but each cloud caps out at 55GB, and who would share which clouds? If our devices share clouds, would they have to sync the same media? That's not really what we want, and it doesn't help me out with my PC backup.

Dreamhost Backup

As a customer of Dreamhost, I get a free-for-the-first 50GB backup plan. That's quite decent. I'm using it already to backup my desktop. I love that the backup is done via rsync over ssh. It's flexible, smart, and encrypts my data on its way to the server in the cloud. But it's a single server in the cloud, and as such, it's a single point of failure. After the first 50GB, it's $0.10 per GB per month.

That's great for the desktop so far. But it doesn't help with the handheld devices unless I have them sync to the desktop, and then have the desktop sync to the cloud. That'd require user action, and that's a point of failure.

DreamObjects

Dreamhost offers high availability space (data is replicated three times, with immediate consistency) in the cloud for effective prices of under $0.07 per GB for developers. As an early adopter, I got in at a promotional rate. For the first 10 GB, DreamObjects isn't the cheapest solution, but after around 60 GB, then DreamObjects becomes a great solution based on price.

DreamObjects don't transfer via ssh, so if I want to encrypt my data, I have to do it myself. For data that doesn't need encryption, I can use boto-rsync which is like rsync. (Note that I linked to a fork that includes the "--exclude" argument.) For data that needs encryption, I'd do it with duplicity.

Of course, it's got the same problem as Dreamhost Backup. It doesn't help with the handheld devices unless I have them sync to the desktop, and then have the desktop sync to the cloud.

The Final Solution

You can't beat free. And you can't beat automatic. While simpler is better, and just choosing one solution would be the simplest, for a cheap developer like me, a hybrid solution looks the most attractive.

Everybody who's got iOS devices will backup the most important type of media that fits into 5 GB per iCloud. After that, we'll have to manually sync our handheld devices to a desktop, and that'll sync with DreamObjects. While I dislike that there'll be a manual step in getting some data into the cloud, I do like that this backup is device independent, and completely within my control.

Implementation Details

From a Linux box, or from an OSX command line, it's even easier than this. But if you're installing into CygWin, assuming you have easy_install installed, here are some installation notes for boto-rsync:

$ easy_install pip $ pip install boto_rsync

A boto-rsync command to DreamObjects looks like this:

$ boto-rsync -a "public_key" -s "secret_key" \ --endpoint objects.dreamhost.com \ --delete ~/dir-to-backup/ s3://bucket/dest-of-backup/

And for Duplicity, you'd need to have installed both librsync1 and librsync-devel from CygWin first. Then:

$ pip install httplib2 oauth $ curl -L http://goo.gl/VBVmB \ > duplicity-0.6.21.tar.gz $ tar xvzf duplicity-0.6.21.tar.gz $ cd duplicity-0.6.21/ $ python setup.py install

A duplicity command to DreamObjects looks like this, after you've configured a .boto file with your credentials:

$ env PASSPHRASE=yourpassphrase \ duplicity ~/dir-to-backup/ \ s3://objects.dreamhost.com/bucket/dest-of-backup

Edit: Here's a follow-up to this post written in 2016.

Entries

Entries