Big Two

What is this?

Big Two is a card game from China originally called Choi Dai Di, or simply Dai Di. It's fun and easy to learn especially if you know poker hands. In Big Two, both suit and rank matter, unlike Chinese Poker, which is even easier to learn. Each player tries to discard all the cards in their hand. When someone discards their last card, the others are penalized points for the cards left in their hands.

Rules

Big Two is played with a standard deck of 52 playing cards. 2 is is the highest rank so the ranking goes: 2 A K Q J 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3. The suit order, starting from highest, is ♠ ♥ ♣ ♦. When played in straights, the two is played below a three.

Scoring varies from place to place. We usually have each player with cards remaining after a game count the number of cards they have against them.

Cutting for the First Deal

Each player selects a single card from the deck. Aces are high during the cut. The owner of the high card gets the deal. The play the rotates clockwise around the table.

Dealing

Each player is dealt 13 cards.

Playing

The player with the 3♦ starts the game. If the 3♦ isn't held by any players, then the next lowest card determines the first player.

First Play: The first player must discard their lowest card individually or as part of a valid “hand”. To make the discard, place the selected cards face up on the table to show the other players. They will have to beat this hand or pass. Valid hands are described below.

Subsequent Plays: Each subsequent player may discard a better hand of the same number of cards as the one shown on the table (if they have such a hand) or pass. For example, if the current play on the table is a pair of eights, 8♥ 8♣, the only play that may be discarded to beat that hand is another pair of a higher value. Since ♠ is the highest ranking suit, then the pair 8♠ 8♦ could beat 8♥ 8♣. All pairs of rank 9 and higher could also beat the pair of eights.

Five-card poker hands: Straights, Flushes, Full Houses, Four of a Kind (with a fifth card), and Straight Flushes can be played, and can be beaten by a higher hand of the same type or by a higher type of five-card hand. For example, a Flush beats a Straight, as does a Full House. The order is: Straight Flush > Four of a Kind > Full House > Flush > Straight .

If everyone passes, then the player who made the last play may start a new trick by discarding a new playable hand of any type. Once a player discards his last card, he has won the trick and each player has to tally his own score. The winner of the trick gets to start the next trick with any valid hand to discard he chooses.

Valid Hands to Discard

- Single Card: A single card may be discarded as a hand. 3♦ is the lowest and 2♠ is the highest.

- Pair: A single pair may be discarded as a hand.

- Three of a Kind: A single three of a kind may be discarded as a hand.

Straight: Straights must be 5 cards long. The 2 is played below a 3 in straights. A straight led by an 8♠ beats an straight led by an 8♥, as does any straight led by a higher rank than 8.

House rules vary as to whether 23456 is a high straight or a low one. The game is called Big Two, after all. Agree to your house rules before you start.

Flush: Flushes must be 5 cards long. Rank is determined by Face value of the highest card. Suit (♠ ♥ ♣ ♦) is used to break ties.

A common alternative house rule is: A flush in a higher suit beats a flush in a lower suit regardless of the ranks of the cards. Otherwise the rank of the highest card determines which flush beats another of the same suit.

- Full House: A pair accompanied by a three of a kind. The value of the full house is determined by the three of a kind. (99944 beats 777KK because 9s are higher than 7s.)

- Four of a Kind: Four of a kinds must be played with a fifth card. The value of the fifth card does not matter. (E.g., 6JJJJ beats 84444 because Js are higher than 4s.)

- Straight Flush: The value of the straight flush is determined by its highest card.

Scoring

While scoring varies from place to place, here's one way: Each time somebody has won a round, the other players have to count the number of their remaining cards, and add points to their current score according to the following rules:

- All cards caught in the hand: 50 points.

- All cards but one caught in the hand: 40 points.

- All cards but two caught in the hand: 30 points.

- Otherwise: Add 1 point for each card caught in the hand.

History

The game was taught to us by Derek and Pei Fluker in Silicon Valley in the 1990s.

From Wipeout to Devs

Wipeout

In 1995, the PlayStation game Wipeout was released, and its influence was massive. It had great playability, music and visuals. The clean and futuristic visuals were designed by The Designers Republic and they were incorporated into all parts of the game, advertising copy and at least one music video.

The music of Wipeout included works by the Chemical Brothers, Fluke, and The Prodigy. The official music video for Fluke's "Atom Bomb" revolves around Ariel Tetsuo, one of the characters in Wipeout. it's a combination of in-game video, animation, effects, and live video suitable for a screening at a rave party.

For years, when returning from San Francisco on an empty 280 freeway with racetrack curves, I'd play Atom Bomb (or just remember the tune) and be reminded of flying by on a Wipeout course looking for imaginary power-up pads.

The Chemical Brothers

Wipeout got me further interested in electronic and techno music from artists like The Chemical Brothers. The Chemical Brothers have a history of innovative music video from creative directors like the legendary Michel Gondry. Their video for "Wide Open" ft. Beck stars Sonoya Mizuno dancing alone in a warehouse as parts of her body become 3D-printed lattice constructions – in one amazing four and a half minute shot. It was directed by Dom & Nic.

The video is worth watching. The music and the dance are haunting on their own, and her transformation to the printed lattice self is on another level. It's amazing.

Fx Guide has an excellent, deep article on the making of that music video, So, just how was that Chemical Brothers video made? There is also a worthy four-minute documentary, "The Chemical Brothers - The Making Of Wide Open" on YouTube:

FX's miniseries Devs

I was already a huge fan of the original series on FX Legion. So when I heard people raving about a new miniseries called, "Devs", I was very willing to give it a chance.

I've just started Devs and it looks to be really good. The main character is played by Sonoya Mizuno, the dancer from "Wide Open"! Oh man, there's nothing but positive associations there for me going all the way back to 1995. Everything from FX, Sonoya Mizuno, to the Chemical Brothers all the way back to Wipeout.

I really hope I like the rest of Devs. ^_^;

PSNation was the source for the Wipeout image.

Chinese Poker

What is this?

This is a fun card game that’s easy to learn. Each player tries to discard all the cards in their hand. When someone discards their last card, the others are penalized points for the cards left in their hands.

If you like Chinese Poker, you may want to try Big Two next.

Rules

Before playing, the players agree to play to a certain score maximum. (Usually 100.) Once any player reaches the maximum the game is over. The player with the lowest score is the winner.

Chinese Poker is played with a standard deck of 52 playing cards. Three 2s and one ace are removed, leaving a deck with 48 cards. Suits and color do not matter. Only the values of the cards matter. Aces beat kings. When played individually, the two is the high card. (It will beat an ace.) When played in straights, the two is the low card.

Cutting for the First Deal

Each player selects a single card from the deck. Aces are high during the cut. The owner of the high card gets the deal. The dealer also gets to make the first play. (“Plays” are described below.) The play the rotates clockwise around the table.

Dealing

- 2 Players: The dealer deals out 3 hands of 16 cards each. Then the dealer gets to choose any one of the three hands. The other player then gets to select one of the remaining two hands.

- 3 Players: The dealer deals out 3 hands of 16 cards each. Each player plays the hand they are dealt.

- 4 Players: The dealer deals out 4 hands of 12 cards each. Each player plays the hand they are dealt.

Playing

First Play: The current player may discard a valid “hand” from his whole hand, or choose to pass. To discard a hand, place the selected cards face up on the table to show the other players. They will have to beat this hand or pass. Valid hands are described below.

Subsequent Plays: Each subsequent player may discard a better hand of the same type as the one shown on the table (if they have such a hand) or pass. For example, if the current play on the table is a pair of 8s, the only play that may be discarded to beat that hand is another pair of a higher value (9s and up). (Four of a kind is a wild hand, an exception, and is described below.)

If everyone passes, then the player who discarded the most recent hand may discard a new hand of any type. (As in the first play.) Once a player discards his last card, he has won the round and each player has to tally his own score. The winner of the round gets to deal the next round. (This can be very frustrating if you’re not the winner!)

Valid Hands to Discard

- Single Card: A single card may be discarded as a hand. 3 is the lowest and 2 is the highest.

- Pairs: A single pair, or sequential pairs, may be discarded as a hand. Any number of pairs may be discarded in a hand, as long as they are sequential. (E.g., 445566 is a valid hand, while 445577 is not because 7 does not come immediately after 5.)

- Three of a Kinds: As pairs, three of a kinds may be played individually, or in groups of sequential values. (E.g., 333444.)

- Full House: A pair accompanied by a three of a kind. Only the value of the three of a kind needs to be beaten in the subsequent play. (99944 beats 777KK because 9s are higher than 7s.)

- Straight: Straights must be at least 5 cards long. They may be as long as 13 cards. The 2 is the low card in straights. To beat a straight, you must play a higher straight of exactly the same number of cards. (E.g., 456789 beats 345678.)

- Four of a Kind: Four of a kinds must be played with a fifth card. The value of the fifth card is the value to be beat by another four of a kind. (E.g., 84444 beats 6JJJJ because 8s are higher than 6s.) Four of a kinds are wild hands and may be played on any other kind of hand!

Scoring

Each time somebody has won a round, the other players have to count the number of their remaining cards, and add points to their current score according to the following rules:

- All cards caught in the hand: 50 points.

- All cards but one caught in the hand: 40 points.

- All cards but two caught in the hand: 30 points.

- Otherwise: Add 1 point for each card caught in the hand.

History

The game was taught to us by Derek and Pei Fluker. We know this is not the same as another gambling game called Chinese Poker.

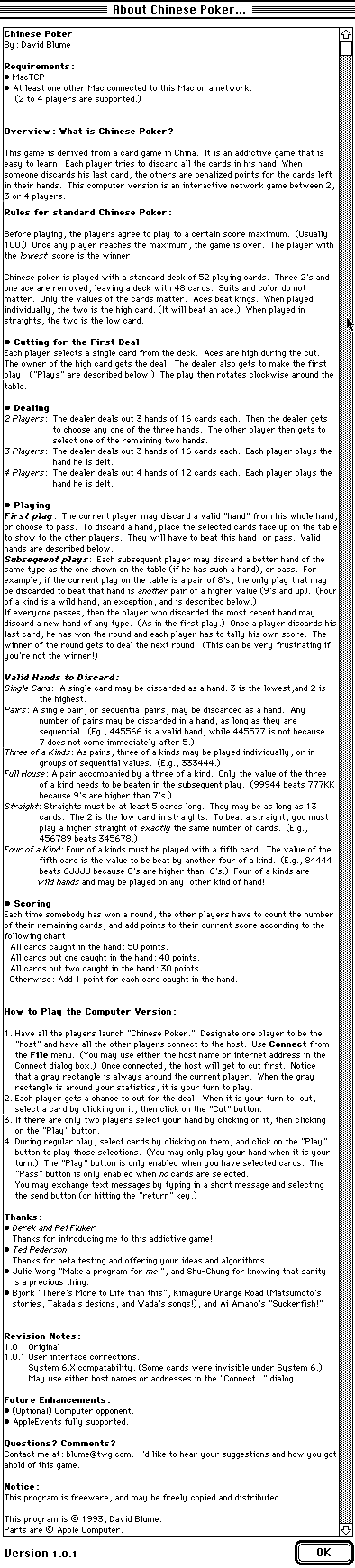

In 1993, I created what may be the world’s first online card game with a GUI interface. Here’s the “About” window for the classic Macintosh version.

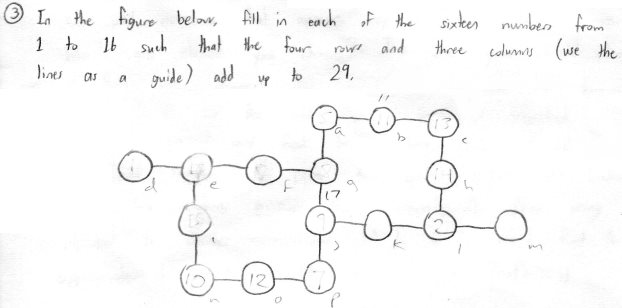

Father's Day Challenge

Here's a puzzle my son put in my Father's Day card. He wrote, "In the figure below, fill in each of the sixteen numbers from 1 to 16 such that the four rows and three columns (use the lines as a guide) add up to 29."

You can tell from the pencil markings that I tried to solve it by hand. But it wasn't long before I thought about trying to solve it with a Python script. There's a naïve script that you could write:

for permutation in itertools.permutations(range(1, 17)):

if rows_and_cols_add_up(permutation):

print permutation

That one just tries every single ordering of the numbers and then presumably checks things like sum(p[0], p[1], p[2]) == 29 in the testing function. The only problem with that approach is that the potato I'm using for a computer might not finish going through the permutations before the next Father's Day. (No, really. There are over 20 trillion permutations to check.)

Fast but Not Exactly Correct

So I decided to attack it from another angle, just look at the rows first. There are four rows, let's call them rows a, b, c, and d from top to bottom. Row a has a 3-tuple in it, b has a 4-tuple, c has a 4-tuple, and d has a 3-tuple. I wrote an algorithm that first finds all the 3-tuples and 4-tuples that add up to 29.

From those sets of valid 3-tuples and 4 tuples, the algorithm chooses a 3-tuple, a 4-tuple, another 4-tuple, and finally a 3-tuple. It assures that there are no duplicate numbers across any of the tuples. Then if that's true, it checks the three columns, and if they add up to 29, it prints the winning results.

And voilà, it worked, and demonstrated that there are multiple solutions, and found them in mere seconds! I saved that initial implementation as a gist. I thought I was done, but the code was bugging me. I knew that while it reflected the way I approached the problem, it was inefficient (it did too many comparisons), it included duplicate solutions (that's the "wrong" part of it), and it wasn't Pythonic.

Correct but Slower

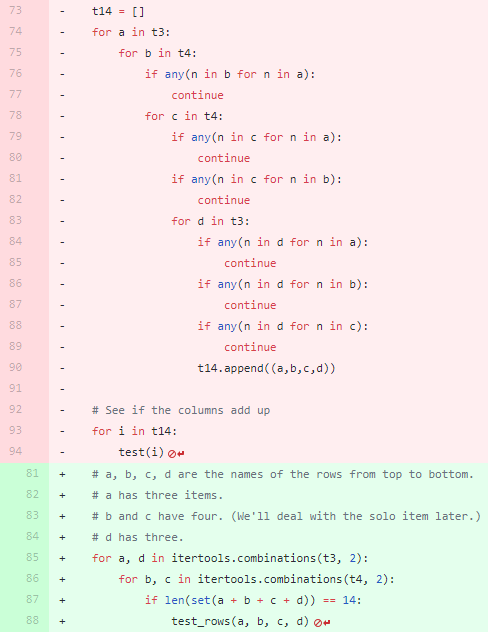

So, a few hours later, I refactored the code, and realized I could replace four nested "for" loops (one for each row) with two loops that each choose two items from their containers (one container of 3-tuples, and one of 4-tuples). And I could check for no-duplicates on one line using a set() instead of explicitly checking for duplicates with "any(this in that)" calls.

The refactor replaced 22 lines of deeply nested code with four lines of simpler code. Not only were there fewer lines, I hoped the program became more efficient because it's iterating fewer times. That's the best kind of change! It's smaller, easier to reason about, and should be faster when executed. It's very satisfying to commit a change like that! The changes to the gist can be seen here:

The red lines are being replaced by the green lines. It's nice to see lots of code being replace by fewer lines of code.

Correct and Fast

I was wrong about it being faster!

Profiling showed that while the change above was more correct because it didn't include duplicate results, it was inefficient because it lacked the earlier pruning between the for loops from the first try. Once I restored an "if" call between the two new for loops, the program became faster than the first run.

for b, c in itertools.combinations(t4, 2):

if len(set(b + c)) == 8:

for a, d in itertools.combinations(t3, 2):

if len(set(a + b + c + d)) == 14:

test_rows(a, b, c, d)

It's very rewarding to bend your way of thinking to different types of solutions and to be able to verify those results. This feeling is one of the reasons I still code.

Here's the final version of the solution generating code.

Photo by William Doyle / CC BY-ND 2.0

Entries

Entries